The Root Causes of Pollution in San Antonio and Greater Areas, Within a General Context of Recycling

Recycle. The word and its various slogans have become buzzwords in recent times, especially in relation to the issues of global warming and environmental sustainability. Many people may know of the latest methods or programs available in their areas to recycle more or become better stewards of their immediate environment through activities like local buying, carpooling, and composting, yet a large disparity still remains between a vast majority of the population and frequently espoused "green" practices.

According to a 2006 survey conducted by Solid Waste Management in San Antonio, and a 2009 survey conducted the City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, San Antonio had a recycling rate of 4% [1,2]. Compared to the national recycling rate in the U.S., which was at 32% as of 2006, San Antonio has a lot of ground to cover [3].

According to a 2006 survey conducted by Solid Waste Management in San Antonio, and a 2009 survey conducted the City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, San Antonio had a recycling rate of 4% [1,2]. Compared to the national recycling rate in the U.S., which was at 32% as of 2006, San Antonio has a lot of ground to cover [3].

- Why all this concern about recycling, and why does it matter?

- What are some factors that encourage or discourage environmentally-friendly behavior (historical, sociological, practical, etc)?

- What can be done to promote (and continue to promote) this behavior and not others?

Why all this concern about recycling, and why does it matter?

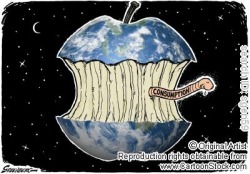

In all their daily interactions and activities, people everywhere produce waste material that must be placed somewhere - the majority of it ends up in landfills, or places where it is incinerated, and once again dumped in landfills. These waste-managing practices contribute to the pollution and degradation of our water, atmosphere (both immediate and global), and environment. Especially because of our fast-paced, industrialized economy (and developing countries trying to model after us), many of us consume material goods at an alarming rate - goods that must be produced from a finite supply of natural resources on our planet. According to one estimate, in the past three decades we have consumed 1/3 of the world's resources [4]. It is posited that if the rest of the world were to consume material goods at the rates we enjoy in the west, we would need anywhere between 2-5 planet earths [5].

These activities are clearly unsustainable. Sustainability has been defined in a myriad ways, but generally it is concerned with leaving enough - and good enough - resources for future generations while providing for the needs of our own in the present. A compelling question by Michael Bell characterizes the concern of sustainability: "How long can we continue to do what we are doing?"[6]. A list of other interesting definitions of sustainability can be found here. By recycling, we are able to divert salvagable materials that would otherwise be dumped as garbage into a landfill or incinerated, which would slow down the rate at which we extract additional raw materials from the earth's finite supply.

The issue of recycling also ties in with the rights and beauty of habitat, which is characterized by the words of Aldo Leopold, who said "A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherswise"[6]. The world's growing demand for paper has, until recent years, led to the deforestation of half of the total area of forestland [6]. Deforestation leads to the loss of biodiversity in the world and increases the extinction rate of species because they have lost a niche necessary to their survival; deforestation also leads to the ground's inability to retain water or prevent soil erosion because of the lack of complex root systems, leading to increased instances of flooding in areas that the logging industry are highest [7], which tend to be in developing countries with fewer means of economic opportunity. Recycling one ton of paper is the equivalent of saving 17 trees, 25 barrels of oil, 7,000 gallons of water, and 3 cubic yards of landfill space [8].

Up until the 1960's, incineration was the preferred method of burning waste material to conserve space in landfills, until the EPA deemed it a source of air pollution. This burning releases greenhouse gases, which accrete in the atmosphere and accelerate the global warming process, along with methane (a by-product of decomposing organic matter), and water vapor. However, Covel Gardens - a landfill site in San Antonio - currently has has a greenhouse gas-collection system in place, which allows gases seeping from the buried garbage to be pumped into a generator that currently provides electricity in 6,000 city homes [9].

Recycling also ties in with the issue of environmental justice, as those with the least power tend to receive the most pollution [6]. From wealthier countries dumping excessive or illegal waste materials onto poorer countries (which accepts them for profit), to the excessive consumption of the average person living in a wealthy country to that of a developing one in areas of food and energy-our consumptive habits increase our rate of resource extraction. Demand for paper in industrialized countries has stripped Latin America and areas of Africa of millions of acres of forestland; unrecycled "e-waste" (waste that comes from electronic products) can leach lead and other harmful chemicals into the water sources where they are dumped, affecting local communities that depend on those water sources for drinking, irrigating, and bathing [10]. This is in line with the trend that people in wealthier countries are better able to avoid the environmental consequences that their activities generate, while those in poorer areas are not, and suffer those consequences [6].

These activities are clearly unsustainable. Sustainability has been defined in a myriad ways, but generally it is concerned with leaving enough - and good enough - resources for future generations while providing for the needs of our own in the present. A compelling question by Michael Bell characterizes the concern of sustainability: "How long can we continue to do what we are doing?"[6]. A list of other interesting definitions of sustainability can be found here. By recycling, we are able to divert salvagable materials that would otherwise be dumped as garbage into a landfill or incinerated, which would slow down the rate at which we extract additional raw materials from the earth's finite supply.

The issue of recycling also ties in with the rights and beauty of habitat, which is characterized by the words of Aldo Leopold, who said "A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherswise"[6]. The world's growing demand for paper has, until recent years, led to the deforestation of half of the total area of forestland [6]. Deforestation leads to the loss of biodiversity in the world and increases the extinction rate of species because they have lost a niche necessary to their survival; deforestation also leads to the ground's inability to retain water or prevent soil erosion because of the lack of complex root systems, leading to increased instances of flooding in areas that the logging industry are highest [7], which tend to be in developing countries with fewer means of economic opportunity. Recycling one ton of paper is the equivalent of saving 17 trees, 25 barrels of oil, 7,000 gallons of water, and 3 cubic yards of landfill space [8].

Up until the 1960's, incineration was the preferred method of burning waste material to conserve space in landfills, until the EPA deemed it a source of air pollution. This burning releases greenhouse gases, which accrete in the atmosphere and accelerate the global warming process, along with methane (a by-product of decomposing organic matter), and water vapor. However, Covel Gardens - a landfill site in San Antonio - currently has has a greenhouse gas-collection system in place, which allows gases seeping from the buried garbage to be pumped into a generator that currently provides electricity in 6,000 city homes [9].

Recycling also ties in with the issue of environmental justice, as those with the least power tend to receive the most pollution [6]. From wealthier countries dumping excessive or illegal waste materials onto poorer countries (which accepts them for profit), to the excessive consumption of the average person living in a wealthy country to that of a developing one in areas of food and energy-our consumptive habits increase our rate of resource extraction. Demand for paper in industrialized countries has stripped Latin America and areas of Africa of millions of acres of forestland; unrecycled "e-waste" (waste that comes from electronic products) can leach lead and other harmful chemicals into the water sources where they are dumped, affecting local communities that depend on those water sources for drinking, irrigating, and bathing [10]. This is in line with the trend that people in wealthier countries are better able to avoid the environmental consequences that their activities generate, while those in poorer areas are not, and suffer those consequences [6].

What are some factors that encourage or discourage environmentally-friendly behavior (historical,sociological, practical, etc)?

Bell makes a strong case that the social constitution of daily life - how we as a human community institute the many structures and motivations that pattern our days, making some actions convenient and others not - is the source of many of our environmental problems [6]. The way our society is constituted (and enforced by the virtue of our unquestioned or unchalleneged participation in it) predicts the kinds of ideas we are likely to encounter, and the behaviors we are likely to engage in. If a trash bin were located closer to a household than a recycling facility, then surely out of convenience we might expect the resident to dispose of his garbage in the trash bin for the lesser effort that it requires.

Convenience is often cited as a factor that determines whether a person recycles or not. The ease of recycling, the proximity of bins, and the availability of recycling programs in an area contribute towards increased recycling rates. One research participant in a recycling focus group expressed a common sentiment, “If we had collections of recyclable materials from home I would definitely recycle more” [11,12].

More often inconvenience was a factor that discouraged recycling, such as the lack of transportation, the lack of bins or a local recycling program, or the learning curve required to understand the different symbols for separating paper and plastics. In the case of a college campus study, a large collection of recyclables tended to attract pests, which interfered with dormitory operations and student life. This temporarily provided a reason for the administration to suspend the campus recycling program until it was better organized. In the absence of a bin, students were “more likely to dispose of recyclable items than go out of their way to find” one [11, 13]. Sometimes the infrequency or inefficiency of recycling collection programs allow trash bins to overflow, and excess recyclables are simply thrown away [11,14].

Knowledge is another factor influencing recycling behavior, which includes knowledge of what the environmental issues are, like those pertaining to sustainable consumerism, greenhouse gas emissions, and the effects of our everyday interactions on the environment whether through the air we breathe, the vehicles we drive, or the chemicals we use. Without this background understanding we can imagine that recycling behaviors, whether newly adopted or not, will last long [15].

Convenience is often cited as a factor that determines whether a person recycles or not. The ease of recycling, the proximity of bins, and the availability of recycling programs in an area contribute towards increased recycling rates. One research participant in a recycling focus group expressed a common sentiment, “If we had collections of recyclable materials from home I would definitely recycle more” [11,12].

More often inconvenience was a factor that discouraged recycling, such as the lack of transportation, the lack of bins or a local recycling program, or the learning curve required to understand the different symbols for separating paper and plastics. In the case of a college campus study, a large collection of recyclables tended to attract pests, which interfered with dormitory operations and student life. This temporarily provided a reason for the administration to suspend the campus recycling program until it was better organized. In the absence of a bin, students were “more likely to dispose of recyclable items than go out of their way to find” one [11, 13]. Sometimes the infrequency or inefficiency of recycling collection programs allow trash bins to overflow, and excess recyclables are simply thrown away [11,14].

Knowledge is another factor influencing recycling behavior, which includes knowledge of what the environmental issues are, like those pertaining to sustainable consumerism, greenhouse gas emissions, and the effects of our everyday interactions on the environment whether through the air we breathe, the vehicles we drive, or the chemicals we use. Without this background understanding we can imagine that recycling behaviors, whether newly adopted or not, will last long [15].

Major Hurdles Making Recycling an Environmental Concern

in San Antonio

Not everyone in society is given an equal opportunity to recycle. People living in poverty already have less advantage to certain goods that others may have. Along with poverty comes frequent hurdles in education. Therefore, less knowledge of the issue and concern of pollution due to lack of recycling. When one does not have the assets to understand the problem, working on a solution is walking in blind-folded.

Many are educated on the matter, and it is not because they do not care about the issue, it is that they are boggled by present traumas in their daily lives. As society leads us, each day we are pushed from one hour to the next, trying to cover all of our tasks without missing a beat. We may think we are "too busy" to worry about the environment as a consequence many will avoid the worry about what they know is an issue, just ignoring what a major problem this will be for our future generations.

Many are educated on the matter, and it is not because they do not care about the issue, it is that they are boggled by present traumas in their daily lives. As society leads us, each day we are pushed from one hour to the next, trying to cover all of our tasks without missing a beat. We may think we are "too busy" to worry about the environment as a consequence many will avoid the worry about what they know is an issue, just ignoring what a major problem this will be for our future generations.

Proper Recycle and Trash Disposers

Should be Available to the Community

Negligance

As we can plainly see in this picture, the trash can is not even 3 feet away. How hard is it to pick up the dropped item that is trash and place it in its place. Every small deed makes a difference.

Works Cited:

1

2

3

4 Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins and L. Hunter Lovins, Natural Capitalism, Little Brown and Company, (1999). Chapter 1. http://www.naturalcapitalism.info/

5 Leonard, Anne. Facts from The Story of Stuff. http://www.storyofstuff.com/pdfs/annie_leonard_footnoted_script.pdf Originally from: Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees, Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth (1996).

6. Bell, Michael. Page 7, 19, 24, 29

7. Worldwatch Institute. 2005. Vital Signs 2005. The Trends that Are Shaping Our Future. New York: Norton and Company, Ltd.http://books.google.com/books?id=XifQ7hby3ekC&pg=PA92&lpg=PA92&dq=worldwatch+institute+deforestation&source=bl&ots=ONBeSRvv63&sig=SUas1U5XZxCR-hS2DeMPusxHsKM&hl=en&ei=h44aS4vuHYy1tgeE_fT2CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CCYQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=worldwatch%20institute%20deforestation&f=false

8. Wagner, Joan. 1995. The 3 R's of Solid Waste & the Population Factor for a Sustainable Planet. The American Biology Teacher, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 88-91.

9. http://covelgardens.wm.com/facility/operations.asp

10. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/hdr_1998_en_overview.pdf

11. Escobedo, Phillip. 2008. Factors Affecting Recycling Behavior: A Review of the Literature.

12. Barr, Steward, Nicholas J. Ford, and Andrew W. Gilg. 2003. “Attitudes towards Recycling Household Waste in Exeter, Devon: quantitative and qualitative approaches.” Local Environment 8 (4): 407-421.

13. Hansen, Lexine T., Michael Kaplowitz, John Kerr, Chelsea McMellen, Lauren Olson, and Laurie Thorp. 2008. “Recycling Attitudes and Behaviors on a College Campus: Use of Qualitative Methodology in a Mixed-Methods Study.” Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research 2: 173-182.

14. Linden, Anna-Lisa, and Annika Carlsson-Kanyama. 2003. “Environmentally Friendly Disposal Behaviour and Local Support Systems: lessons from a metropolitan area.” Local Environment (8) 3: 291-301.

15. Hardin, Russeli. 1998. “Garbage Out, Garbage In.” Social Research 65 (1): 13-24.

1

2

3

4 Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins and L. Hunter Lovins, Natural Capitalism, Little Brown and Company, (1999). Chapter 1. http://www.naturalcapitalism.info/

5 Leonard, Anne. Facts from The Story of Stuff. http://www.storyofstuff.com/pdfs/annie_leonard_footnoted_script.pdf Originally from: Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees, Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth (1996).

6. Bell, Michael. Page 7, 19, 24, 29

7. Worldwatch Institute. 2005. Vital Signs 2005. The Trends that Are Shaping Our Future. New York: Norton and Company, Ltd.http://books.google.com/books?id=XifQ7hby3ekC&pg=PA92&lpg=PA92&dq=worldwatch+institute+deforestation&source=bl&ots=ONBeSRvv63&sig=SUas1U5XZxCR-hS2DeMPusxHsKM&hl=en&ei=h44aS4vuHYy1tgeE_fT2CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CCYQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=worldwatch%20institute%20deforestation&f=false

8. Wagner, Joan. 1995. The 3 R's of Solid Waste & the Population Factor for a Sustainable Planet. The American Biology Teacher, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 88-91.

9. http://covelgardens.wm.com/facility/operations.asp

10. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/hdr_1998_en_overview.pdf

11. Escobedo, Phillip. 2008. Factors Affecting Recycling Behavior: A Review of the Literature.

12. Barr, Steward, Nicholas J. Ford, and Andrew W. Gilg. 2003. “Attitudes towards Recycling Household Waste in Exeter, Devon: quantitative and qualitative approaches.” Local Environment 8 (4): 407-421.

13. Hansen, Lexine T., Michael Kaplowitz, John Kerr, Chelsea McMellen, Lauren Olson, and Laurie Thorp. 2008. “Recycling Attitudes and Behaviors on a College Campus: Use of Qualitative Methodology in a Mixed-Methods Study.” Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research 2: 173-182.

14. Linden, Anna-Lisa, and Annika Carlsson-Kanyama. 2003. “Environmentally Friendly Disposal Behaviour and Local Support Systems: lessons from a metropolitan area.” Local Environment (8) 3: 291-301.

15. Hardin, Russeli. 1998. “Garbage Out, Garbage In.” Social Research 65 (1): 13-24.